This past year was huge for child care.

In February, Congress finally reached a bipartisan agreement on the federal budget. The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 not only provided billions in “new” discretionary funding for the next two fiscal years but specifically pledged to double investments for child care.

In March, Congress then passed the FY2018 Omnibus bill, which included a historic $2.37 billion increase for the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG). Six months later, Congress provided an additional $50 million to CCDBG while simultaneously increasing funding for other key programs like Head Start ($200 million).

These wins in early childhood funding should certainly be celebrated. But this celebration also needs a caveat: that for FY2020, we need to ensure this funding remains a priority for the 116th Congress. Here are three reasons for concern about CCDBG investment next year:

Reason #1: New Membership

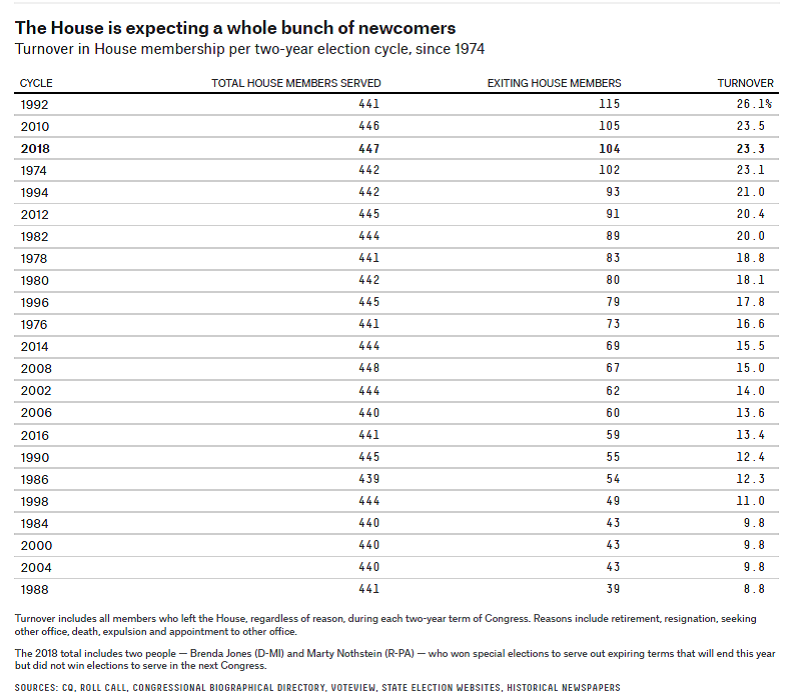

The 2018 midterm elections last November were historic for many reasons, among them being the number of new members entering Congress next year. In fact, the House of Representatives will experience one of its highest rates of turnover in 40 years, as demonstrated in the chart below.

With new members of Congress comes new opportunity. However, a high rate of turnover also means a loss of institutional memory. This could impact long-term support for CCDBG since this is, by far, the highest rate of member turnover since its 2014 reauthorization.

New members will need to be educated not just on how CCDBG benefits families and providers, but also on its history. They need to know that states were struggling after the reauthorization because funding was not added alongside the new standards. They need to know that 2015 and 2016 saw historic lows of children served by the grant. Finally, they need to know that CCDBG is still underfunded, even with the generous increase, and that returning to previous funding levels would be disastrous for children and families.

Reason #2: The Rumor

After the historic increase of CCDBG for FY2018, an interesting rumor began to take shape: that this was only a one-time increase, so states should avoid long-term investments. As a result, some states chose to prioritize one-off projects with their additional CCDBG funds, or even hesitated to use them at all.

To be clear, a bipartisan group of members of Congress never intended for the CCDBG increase to be temporary. Instead, FY2019 spending levels will be the new starting point for negotiations.

While the appropriations process will never be fully predictable, the concerns sparked by the rumor may become a self-fulfilling prophecy. If states cannot demonstrate a need to maintain a strong CCDBG investment, it is more difficult for Congressional appropriators to convince their colleagues to do so. Not only do we need to dispel this rumor, but we then need to demonstrate to Congress, through data, research and stories, why maintaining CCDBG is necessary for children and families.

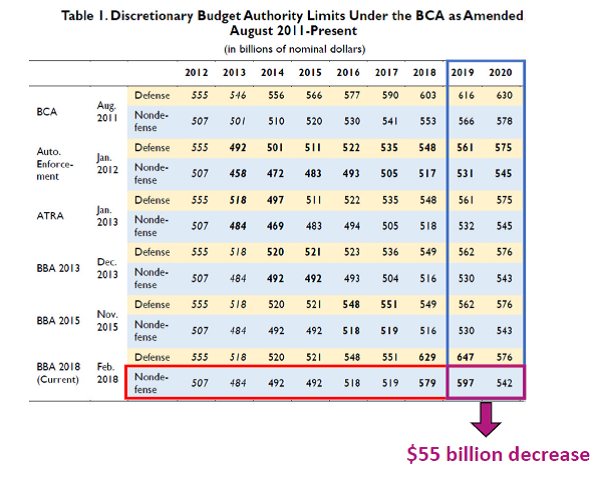

Reason #3: The Spending Caps

A crucial component of CCDBG’s historic increase was the lifting the non-defense, discretionary spending caps set by the Budget Control Act of 2011. The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 lifted these spending caps until the end of FY2019. As per the chart below, these caps would change for non-defense, discretionary spending from $597 billion for FY2019 to $542 billion in FY2020—a decrease of $55 billion! This is concerning not only for CCDBG, most of which is considered discretionary spending, but for all social programs.

This means that advocacy for FY2020 will need to be twofold. First, the budget caps must be lifted to ensure that discretionary spending is not substantially decreased. If this happens, then our advocacy efforts for maintaining CCDBG funding is more likely to be successful. If not, then there will be fierce competition amongst all social programs for the little funding available.

Of course, this is all easier said than done, especially with the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017. This past year saw a substantial increase in the federal government’s deficit, putting pressure on members of Congress to cut spending wherever they can.

So what can you do to help overcome these obstacles?

Here are three options:

1) Educate members of Congress. New members do not have familiarity with the history and function of CCDBG. Even experienced members may not be well-versed in CCDBG either, especially if they sit on different committees. Coupled with the notorious high rate of staff turnover on Capitol Hill, it is always worthwhile to get them caught up to speed.

2) Amplify the message. Sustained, long-term CCDBG funding could be at risk and we need as many voices as possible to join us. However, we recognize that CCR&Rs often have their plate full supporting families in their communities.

Let us help. Joining Child Care Works, our advocacy arm, can provide resources for expanding your reach. We can even set up an Action Alert Center for you. To learn more, email our team.

3) Advocate directly to lawmakers. This spring, Child Care Aware® of America will host the Child Care Works Summit on April 3-4, 2019. This event will welcome CCR&Rs, child care providers, family advocates and other partners to Washington, DC, for a day of training and sessions, followed by a day on Capitol Hill to meet with your lawmakers.

We hope you can join us for this crucial time for advocacy. Our message is only effective when it comes from the voices in the community that come together to share our message with Congress. For more information, including registration, click here (Early Bird Registration ends on January 1, 2019).